Some carcinogens can cause cancer without directly damaging DNA: a new study from the Cancer Grand Challenges Mutographs team challenges a long-held view on the early development of a tumour.

For years, research has focussed on mutations – damage to our DNA – as the driving cause of cancer. As a cell goes through life, its DNA picks up a unique combination of mutations, from natural cellular processes or from exposure to cancer-causing factors in the environment – including carcinogens like tobacco smoke. This pattern of damage is known as a ‘mutational signature’ and, depending on the amount and type of damage, can cause a cell to become cancerous.

But new findings from the Mutographs team are challenging this narrow, long-held view: cancer’s origin is often much more complex than the direct effect of a carcinogen on DNA.

The study, published in Nature Genetics, sought to match 20 known cancer-causing chemicals in our environment with their corresponding mutational signature in mouse DNA. While all 20 chemicals caused cancer, only 3 left a distinct pattern of mutations.

Strikingly, 17 left no distinct pattern of DNA damage, suggesting they cause a cell to become cancerous in other, indirect ways – perhaps influencing inflammation in the surrounding tissue or interacting with immune cells to alter their behaviour.

The remaining 3 chemicals – a metal, an industrial chemical and a compound often found in polluted drinking water – were linked to distinct mutational signatures, both in mouse and human DNA.

The team’s thought-provoking study suggests we need to look beyond mutations as the driving cause of cancer: DNA damage is just one piece of the complex puzzle that is cancer development. A major step towards putting the pieces together, the findings could ultimately transform our ability to prevent and treat cancer.

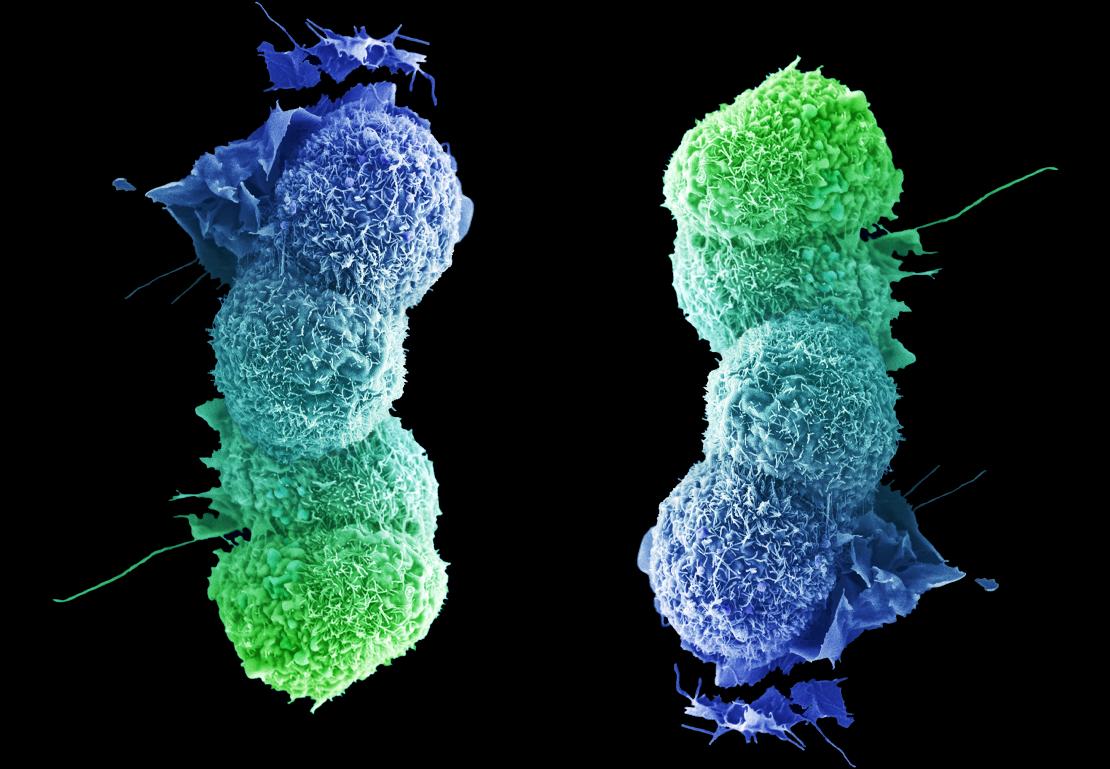

Image: Lung cancer cell, full credit to LRI EM department.